1.01

There are several guides to the Blanket Licences, the system TV companies in the U.K. use to licence music for their programmes. For the very best of reasons they try to impose some sort of order on an area of labyrinthine complexity. (One of these reasons is to avoid going on and on… which the following explication does rather).

Blankets are best suited for production, (library), music specifically composed and recorded for synchronisation with other media.

If you wish to use music which has been released commercially you have to follow the rules.

- Find the track in the relevant music rights databases. (Start with those belonging to the PPL & PRS)

- If the details are incomplete, partial or contradictory find who owns or controls the track and check if it’s covered under a blanket agreement.

- If that fails, then choose something else.

Sometimes there are strong creative reasons for hitting on a specific track and you don’t want to give up before exhausting every avenue.

What follows is emphatically not a guide to unravelling the skein; there are simply too many threads to follow. Instead, it tries to explain why you’ve arrived at a dead end and hints at ways forward.

1.02

The blanket licences currently employed to smooth the process of incorporating music into UK TV shows are becoming increasingly difficult to use. The causes are twofold. Firstly, the nature and delivery of media internationally has changed so drastically in the last few years the blanket, being such an ungainly beast, hasn’t been able to keep up with current industry requirements. Secondly, there is so much contradictory data underpinning the implementation of the blanket it makes Sisyphus feel he got a good deal.

Opinion differs on big data. It is either a tool of Balaam or the answer to the global marketers’ prayers. The truth lies somewhere near the middle. Used crudely it is helpful in predicting trends, micro analysed the only pattern it reveals is that different data collection methods have a greater influence on the results than the data itself provides.

I believe that, despite the best efforts of the societies, the blanket licence model will gradually become a niche scheme suitable for strictly local use and that in most cases the programme maker will need to scrutinise the rights situation much more thoroughly. If the programme uses a lot of music, they may be best advised to hire a professional who knows their way around the databases to undertake the work involved.

Of course, it’s an easy thing to say but, since using music covered by the blanket is designed to save money, the above advice seems to defeat the object. The problem lies with the misconception that the “blanket” consists of a list of all the tracks which can be used in TV programmes without additional payment. (Even this statement is only partly true). They believe a music supervisor has privileged access to this list and can tell them, after a quick look, if they can use a piece of music with impunity.

It’s actually the other way round. You first choose a piece of music then investigate who controls the rights to that track. If all the rights have been assigned to the PPL and PRS for Music then you can use the track. However, ensuring that the information you have gathered is correct is entirely your responsibility.

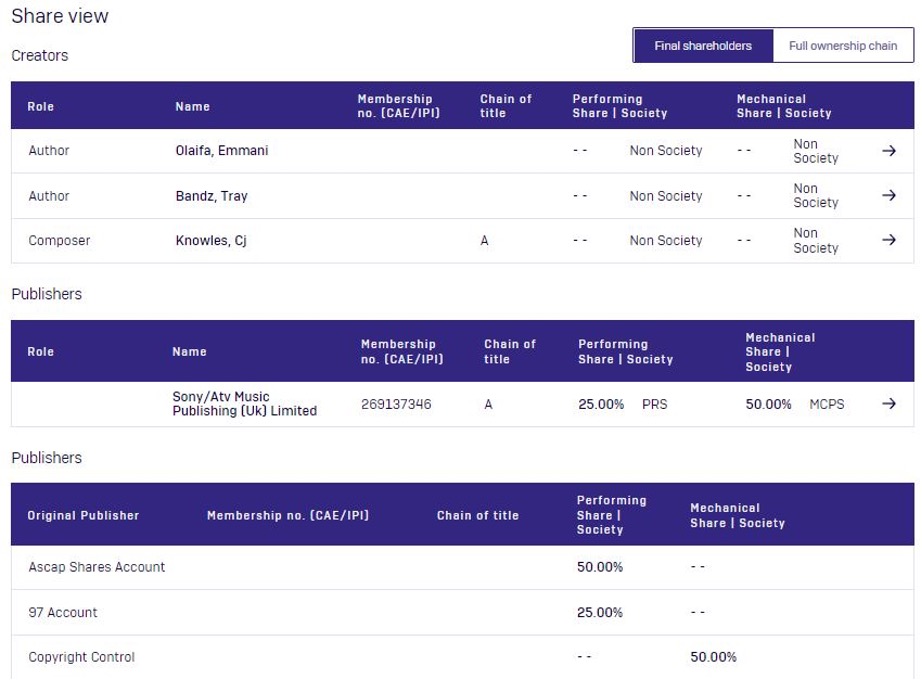

The first port of call is usually the PRS for Music database. A quick look at “Energy,” a track from Beyonce’s latest album reveals:

If you can work out if this track can be used under the blanket, you can move onto the next… and so on for the other half dozen tracks planned for episode one.

1.03

Blanket Licences, so far as music is concerned are the agreements negotiated for a pre-agreed, (and often undisclosed), sum between those large organisations who control the requisite music rights and those large scale users who feature music in their productions. In the UK PRS for Music, (an unholy amalgamation of the PRS and MCPS), has deals with major broadcasting groups. There’s also a mini off the shelf version which can be utilised by the Independent Production Companies.

Just about everything, after this bland and somewhat disarming statement, gets messy.

Guidewise, a good place to start is the Channel 4 guide. It is thorough and well written: (https://www.channel4.com/media/documents/commissioning/COMMERCIAL%20AFFAIRS/C4MusicGuide2014.pdf) For a quick insight check out its simpler cousin, the Bluffers Guide: (https://www.channel4.com/media/documents/commissioning/COMMERCIAL%20AFFAIRS/MUSICTHEUNIVERSEANDEVERYTHING_C4MUSICGUIDE.pdf)

The correct guide for your programme depends on the broadcaster for whom you are making your programme. Each blanket has its own quirks. For example if you are working with Channel 4, there is a fee payable for each track used. With the BBC, there are no fees because the BBC pays a larger amount to the collection societies for the right to use the music.

These and similar guides take you through all the steps required to find out if the commercial tracks you want to use are covered by a blanket licence. However, they are so full of error traps followed by a recommendation you contact the actual rights holders, you are often none the wiser about how to go about it.

The field is so complex, learning how to find the correct information from scratch could take you longer than the time it takes to make the programme. If there are a number of titles, use an experienced music supervisor. If there are just one or two titles or you want to dip a toe into the rights quagmire, read on.

Rather than a straightforward list, these guides offer a seemingly never-ending checklist of criteria all of which must be ticked off before you can be sure the track is covered.

Current media demands access to content 24/7, worldwide, forever, on any device whether it’s been thought of yet or not. Already this is way more than the blankets cover.

1.04

In the UK, the best known blanket agreement is the BBC Blanket Licence. This started out in 1923 as an agreement between (primarily) the record companies and BBC Radio to play records without having to seek permission from the rights holders each time.

In the good old days, which means mostly the hundred years before the eighties, the music creators sold their talent, (often literally), for the price of a breakfast. Recordings belonged to the record label, publishers owned the compositions and that was pretty much that.

Inconveniently a new generation of musicians heard stories of mafia linked moguls helping themselves to copyrights and a plethora of hugely talented artists were looking for barrels to scrape. Even the biggest group in the world were powerless to extricate themselves from a fifty fifty publishing deal pouring millions into the coffers of a man who had a half decent singing voice and an ear for a hit.

As commercial music became a more regular feature in BBC TV programmes, the blanket agreement was extended in 1937 to include the use of commercial music in their programmes. Intermittent renegotiations over the decades have enhanced it to cover the various download and streaming options demanded today.

Whether a blanket agreement covers a piece of music depends on the rights being granted by the owners of the recording and those of the underlying composition to the respective organisations. It often also depends on you being able to find out who these rights holders are.

Therein lies the rub. This depends in turn on the information being accurate, up to date and available. In the U.K. the principal source for recording rights owners is the PPL. Public Performance Ltd. is the organisation record companies and independent music producers join to collect the money paid by broadcasters for playing recordings. The Performing Rights Society is the section of PRS for Music that collects on behalf of and pays to the composers and publishers their shares. Both organisations maintain comprehensive databases.

To be fair the world’s collection societies have on their databases many millions of songs and the majority of these registrations are within spitting distance of accurate.

1.05

If you have been commissioned by a UK broadcaster to make a programme which the broadcaster will own outright, the blanket route is the way to go. If they are partly funding a programme but are limiting their rights to the UK so you can sell the programme to overseas broadcasters and/or distributors, then the blanket will only provide you with some of the rights you need and you will have to pay additional fees to the rights holders to secure additional rights. Unless you are absolutely confident you know the future landscape of media do not risk relying on the blanket agreements and with the possible exception of theatrical, secure all media, worldwide in perpetuity directly from the rights holders.

If you are making the programme independently with a view to selling it to broadcaster(s) / distributor(s) it is not worth trying to shave rights to save pennies. you should secure all media, worldwide in perpetuity from the very start. You could exclude theatrical but remember, that could prevent you screening at film festivals and other public events in the future.

It’s arguable, so far as most radio and TV music programmes are concerned, to believe that the artists and writers will welcome the exposure not to mention the money. However, it has long been recognised that fixing a piece of music alongside a visual image is a different matter entirely as it can link the music to something distasteful to the musicians concerned. And in this case their opinion matters. It’s their song and if it becomes inextricably linked to something unsavoury it can change the way a song is regarded forever – and that decision should be the prerogative of the artist and writer only.

Whilst distinguishing between audio only broadcasting and any medium where music is associated with visual images is fruitful, the difference between film and TV is fast disappearing. The idea that a broad licence where approval is not required can apply to TV programmes but not to theatrical films screenings has become untenable. The hybrid approach of licensing in some territories via a blanket licence and the remainder on a territory by territory basis is frankly absurd.

1.06

Blanket licences are only workable where there is an acceptable local model for collecting income, basically a collection society by another name, which has a reciprocal arrangement with the equivalent society in the originating territory of the licence.

The United States refutes the practicality of a blanket as it is limited in its scope and they want to be able to exploit their programming in any way possible, other countries won’t participate and still others haven’t anything more than the barest bones of an equivalent to the PRS. Then there are the failed or semi failed states that have no copyright law at all. The idea that the blanket licence covers the world excluding North America is yet another absurdity.

PRS for Music has reciprocal arrangements with approximately 100 countries, that’s about a third of the countries in the world. Providing the primary broadcast is in the UK, the music is cleared for use in these countries. You will need to check the terms of your agreement with the overseas broadcaster to see which rights they require and check with PRS for Music if these rights are covered. If not you will be sent back to the rights holder to clear these additional rights directly.

The U.S.A. based broadcasters will always licence for WW, All Media, in perpetuity, (and pay well for the privilege). You may wish to do the same.

A quick google search found seventeen definitions of North America and none of these pertained to copyright. Without a legal definition which is acknowledged and accepted by both sides, (or in the absence of this, one which would be recognised by the governing jurisdiction), it is best to list countries rather than use convenient but vague constructs such as Middle East and Australasia.

Not all people on the copyright side of things could list the actual countries which constitute North America with absolute certainty. If you have any doubts you are advised to check and, if your doubts are sustained, licence the music directly with the rights holders for the countries concerned.

1.07

It’s not only the trustworthiness of the collection societies’ information that is problematic, it’s the actual ownership of the rights.

First the rights in the Recordings. In the two and a bit centuries that the notion of copyright has been established, fixed recordings have only existed in any substantial form since the 1920’s. While the technology had been around since 1896, the record as we know it today only really took off when the original patent expired in 1919 And the door was open for any company to produce the discs.

For the next fifty years the record companies paid for making the recordings. By this we mean hiring the musicians, the recording venue, the technicians and equipment, not simply paying for the manufacturing – the result of which was outright ownership and no obligation to pay royalties. Making records was an expensive process and no one foresaw the day when a single admittedly rather clever individual could by pressing buttons on a machine the size of a laptop could recreate the sound of the largest orchestra.

Not so long ago all you needed to do to find if a track would clear under the BBC Blanket Agreement was check who owned the recording. It was assumed the MCPS already controlled the publishing rights. They had an internet interface with PPL known as Fastclear. If the record label was a member, then that was enough for the Beeb.

By the 90’s just over half of records released were on independent labels. Nothing wrong with that of course but they tended to be a bit slack in the paperwork department. One of two things happened to most indie labels. They were swallowed by bigger labels and as is the nature of food chains ended up as minor unregarded constituent parts of the largest predators – or they disintegrated leaving any verifiable claim of ownership as difficult to find as unicorn doo dah.

Even that simplifies the picture. Moderately successful records, (and in the U.K. moderate success could be as truly moderate as a single play on John Peel’s show), were often licensed for release on one of the million indie compilations put out around the world and subsequently found themselves incorrectly registered on a database somewhere.

At this point it gets worse and brain cells begin to dissolve. In an attempt to consolidate their information, the various collection societies have taken to ingesting data from their compadres. Aware of the dangers of letting one registration take precedence over another, their databases permit multiple registrations.

You have a song title and artist name… so no room for confusion now? Except The Beat, the ska revival band who had a bunch of top ten hits in the U.K. had to change their name to “The English Beat” when they toured the U.S.A. because there was already an American band called “The Beat,” (which had to change their name to “Paul Collin’s Beat” when they toured the U.K.). It might have been an idea for The Beat to keep the name “The English Beat” when they came back but it sounded naff and anyway it could easily be mistaken for the “London Beat” which had formed in the meantime and “The Birmingham Beat” sounded even naffer. None of which were any better than “The British Beat” which was forced upon them when they played Australia.

So, if the name of the band isn’t immutable at least their connection with a song isn’t going to any confusion. Take their biggest hit, “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You.” With only a hundred or so versions, (not to mention all the foreign translations), there’s no chance of error there either…

Wouldn’t it be great if there was some unique code that inextricably linked an artist to a specific recording of a song? You could call it the International Standard Recording Code. So long as you made it completely clear that the code was issued by a responsible body and related only to that combination of artist and recording, then clearing using the specific ISRC would avoid errors.

Except the responsible body entrusted with the task… is the record company. Most record labels understand that the PPL, a parallel organisation to the PRS, collects money on behalf of labels and recording artists when their music is played on the radio and that a block of the ISRC identifies them as the owners of the recording.

They automatically assign their own ISRC to a recording when they release a recording. Bypassing which ISRC should be used when a specific recording has been licensed from another’s company, the new ISRC signals a new and distinct recording. Consequently, the same recording assumes a unique status and as the equivalent societies around the world exchange data, the databases around the world become populated with multiple “records” of the same ahem… records.

Of course, they may not be the same. If it’s the kind of release that benefits from remixes or, in the old days, foreign language versions, (I suppose the modern equivalent is the “clean” and “unclean” versions), each should have its own ISRC. So the different registrations could be the same track or could be different. They could indicate different ownership rights or a misunderstanding of how ISRC’s work. Who’s going to listen, who’s going to check? Who’s going to be up the proverbial creek paddleless if they licence the wrong version from the wrong rights holder?

Back in the sixties the backing tracks of most pop singles were provided by itinerant Session Musicians who spent their days rushing from studio to studio playing on just every record issued. It was all cash in hand and few, if any, paper records were kept – which is why Jimmy Page is rumoured to have played on so many. If he’d actually played on as many records as claimed today his fingers would be worn to stumps.

These days session musicians are supposed to fill out a consent form which provides for additional payments if the song is “re-used”. Explanations of session rates and consent forms are essays for insomniacs but in brief, the members of a band signed to a record label assign their entire performance rights to the label and there are no additional musician fees to be paid however the music is used. Session players, on the other hand only assign the right to use their performance on the commercial exploitation of the recording. This is a fancy way of saying that if the recording is used in any other way, for instance on an advert, in a dramatic TV programme or film, the music is being “re-used” in a way not initially intended.

If you are using a blanket agreement, guides mention you should, “ensure the musicians are bought out or they are band members,” or words to that effect. They mostly don’t tell you anything else. The BBC and ITV blanket licences include the session players union fees for the commercially released recordings. All the other broadcasters, Channel 4 included, are currently (in 2022) required to pay an £25.15 per 30 seconds use (plus a 15% admin fee plus VAT). In other words, if a musician is not bought out or a band member then you would be liable to pay, (usually via the Musicians Union), an additional fee. Theoretically you are supposed to contact the MU with details of each recording and check with them if they should invoice you. You’d be surprised how often the answer is yes. Most people using the blanket agreement don’t realise how many holes there are in the blankets. This is just one of them.

When an artist signs a record agreement and subsequently records and releases a record, the last thing the record company wants is for them to re-record a soundalike version the moment they are off the label so they came up with the Rerecording Restriction. One of the glories of pop music is the one hit wonder so it’s not uncommon for an artist to have had major international success and just a short while later find themselves short of friends.

While there’s still oodles of cash coming in, the record company can’t have the artist getting any, can they? (Check out: https://www.marktavern.com/blog/2020/8/1/an-artists-guide-to-royalties-recoupment-amp-cross-collateralization), so there’s a clause in their contract stating they can’t re-record anything already released for at least five years.

It’s not unusual for an artist to try and re-record as exact a copy of the original as they can manage as soon as they’re allowed. Nor is it unusual for them to encourage its use rather than the original. If the artist controls some or all of the publishing the encouragement can be a subtle as arguing with a sledgehammer. It’s not a problem if you’re licensing within the narrow confines of the blanket but the reason for this diatribe is that the blanket doesn’t cover anything like enough nowadays. If you made a film using music licensed under a blanket agreement and an international streaming company comes a calling, you’re screwed.

Re-recording used to be thought of as faintly embarrassing but now Taylor Swift has re-recorded her entire back catalogue the cat’s out of the bag and everyone’s doing it.

1.08

Of course, it’s much more complicated when it comes to the Publishing.

Once upon a time a song was largely the product of just one or two people strumming a piano and rhyming laughable with photographable. Then The Beatles came along with a very large spoon and stirred things up by doing both. Until then songwriters wrote songs and artists performed them. All nice and neat.

The Beatles’ novel approach of writing their own songs quickly caught on and in the egalitarian 60’s everyone in a group, (even the drummer), got a writing credit. Licensing was still easy enough when they were all with the same publisher but alongside song writing everyone was learning about “musical differences” which led to writing with other people or even, heaven forfend, writing with other people who had other publishers.

Imagine having to approach three or four rival publishers to licence a single song. Imagine, now sampling is rife, having to approach twenty three different publishers. Actually, we don’t have to imagine it; we did it a couple of years ago. It’s doable of course, you just have to know who all the writers are and how to contact them. It only took a year.

This is where it gets tricky. Going back to the 50’s and 60’s the old school writer would grab the sheet music from the previous night’s stint at the piano and rye and head down to Denmark Street, pound out his latest hit and sell it for ten bob so he could get a decent breakfast and a pack of Woodbine.

Scroll on twenty years and pop was the big thing. Millions could be made and competition was fierce. A new breed of publisher was rewriting the rules. One of the new ideas was letting the writers get their rights back after twenty years… or even less.

Great for the writers. Painful for the publishers who had to give up the rights to some huge songs. Disastrous for collection societies who had to cope with hundreds of thousands of changed registrations.

Where’s Willy? (Willy is Wally’s brother who doesn’t have a striped jumper)

The entire history of music publishing is one of disappearing writers, of countless millions being collected but nowhere to send it. At least the publishers had the comfort of knowing they owned the rights and could keep the money in trust for when the writer recalled how he wrote a hit fifty or so years ago.

Nowadays the publisher may cease to own all or part of a song and the rights will automatically “revert” to the writer. If they have written all or part of a money making song the publisher will usually try to retain the rights but if they’ve lost track of the writer, then there may be no one to speak to to secure the rights you need.

At this point you may encounter a variety of opinions on why it will probably be ok to use the song and sort out the money later. Most will be wrong, some may be “a matter of opinion,” (which ultimately may need a court decision so it could be an expensive opinion). If you can bypass the various gatekeepers and your programme makes it to the screen, the sheer amount of content out there means the odds on a copyright owner spotting the use is low so you just might get away with it. Mind you, if you do get caught and the owner doesn’t approve of the use…

Be warned, most distributors and broadcasters make it an obligation for the production company to clear the rights. They don’t care how you do it or how much it costs you, it’s one less obstacle in their way. Of course, they are completely right. We’ve just been asked to help out with a claim that’s holding up the release of a film. Neither the production company nor we think the claim is valid but that doesn’t stop everything grinding to a halt until the dispute is formally resolved. The distributor won’t release the delivery payment and the production company will probably go bankrupt in the meantime.

That said, there are ways of using music and protecting yourself from litigation. There’s such a thing as an orphan work which in the U.K., providing you follow the correct procedure can protect you. It’s most often used for unattributed photographs where it’s clear they would still be in copyright, (when the photograph was taken is frequently obvious), but the photographer impossible to trace. It has been used for music but rarely. At the other extreme is a full due diligence which requires sufficient documentation to satisfy a court without too much in the way of arguments.

If you’ve had a thorough stab at finding the missing rights holder you could possibly resort to your Errors and Omissions insurance policy. It’s not enough to do a quick Google. Finding missing writers is, not something anyone can do, you have to know under which stone to look and exhaust all reasonable avenues before an insurance company is satisfied you’ve done enough. Only last year we failed to track down one of the writers of a number one hit and a lucrative licence fell by the wayside. The insurance company could not accept that someone who had a share of a million seller would stay lost for long.

1.09

If all the above wasn’t complicated enough, the ever inventive music community got into recycling in a big way. It wasn’t a new idea. While not an isolated concept, the best known modern example is the early practice of versioning in reggae. Difficult to pin down exactly but take your pick of Jamaican bands in the sixties putting instrumental versions of their songs on the B side and DJ’s toasting over the top or the early Kingston studios recording backing tracks then inviting singers to lay vocals on top. Both were dubbed onto acetates and played over sound systems in street venues to see which were the most popular and merited full scale black vinyl runs.

The same backing track can be owned by a studio or individual or shared with an influential performer. Compositions similarly can have numerous writer shares depending on who did what and when. Licensing ska, reggae and their progeny is something of a minefield.

Much the same applies to samples. If you’re using a track that contains a sample, (or you suspect it does), then make sure it’s been cleared. Don’t assume. Whether it’s wishful thinking or sheer bravado many a musician believes that if a sample is short or deconstructed it isn’t copyrightable. Not true. Just because they haven’t been caught yet doesn’t mean you won’t. And don’t forget that many a sample from a recording contains elements of the original underlying composition so that may need clearing as well.

1.10

If it’s for a film you have no choice but to start with the basics. You need to licence worldwide, all media, in perpetuity. Even If you’re sure this is as thoroughly covered as legally possible, each licence needs to have a strong indemnity clause in case the licensor has purposefully or inadvertently misled you about their ownership of the rights. You also need to make sure that there is no possibility of anyone serving an injunction on the film by including a carefully worded clause in the licence which precludes this.

It sounds scary but there are a good number of experienced music supervisors in the U.K. who can help you. Ca canny though. Music Supervision isn’t one of those professions where there’s a formal qualification and it’s a popular job description with wannabes. Check IMDB and make sure whoever you’re trusting has at least a dozen credits as music supervisor with creditworthy projects. (Nothing against up and comers with less, but make sure they’re under the wing of someone who knows what they’re doing).

Where a blanket or quasi blanket is part of the mix, the broadcasters make it clear it’s down to you to make sure there are no loose ends.

The BBC covers its derrière in the definition of “Commercial Work” by stating that the licence only applies to works owned by MCPS members and, if there’s more than one writer, then only the part of the composition owned by an MCPS member. So if there’s a portion of the song that’s not MCPS, even if it’s just one writer and less than 1%, (such as the use of a sample), then until you licence the missing slice directly, that particular song is out of bounds.

The Channel 4 guide to clearing music is more approachable and not unhelpful but is full of coulds, shoulds, mights and may be’s. Perhaps it doesn’t like to spoil a party but instead of warning you may hit brick walls, (which it cannot help you over or around), it points you in the right general direction without actually telling you how to go about it. Channel 4’s guide at 34 pages long is a triumph of hope over experience and culminates with “This is assuming, of course that you are able to track down the rights holders in the first instance. Obscure labels and artists can be difficult to trace and may not have even a basic understanding of music copyrights. Do not assume that a license can be arranged overnight. If time is an issue, your best bet is to replace the track with a clearable (100% PRS/PPL registered) one.” Good advice.